Friday, 26 May 2017

MP encourages parents to support children's reading

With the forthcoming "snap" election it is really heartening to know that an MP has spoken out about the importance of parental encouragement for reading. Sadly, it is not anyone in the UK, but then at the moment we do not actually have any MPs, we just have contestants for the role.

This particular MP is Mr Edwin Nii Lante Vanderpuye, the Member of Parliament for Odododiodoo Constituency in Ghana. In his speech for 2017 International Children's Book Day he urged parents to promote a reading culture for their children and he told children to "read, do not stop reading, read anything at all". Mr Vanderpuye carried on with reporting the library services available in the area, which includes a mobile library that visits schools. To read more about it see:

https://www.newsghana.com.gh/inculcate-reading-culture-in-your-wards-mp-urges-parents/

If only our potential MPs could be so passionate about reading and libraries in their campaigning. There is a chance to encourage them. CILIP is spearheading a campaign to get all parliamentary candidates to state that they will use evidence base facts in their electioneering.

https://www.cilip.org.uk/advocacy-awards/advocacy-campaigns/facts-matter

Why not ask them to commit to keeping libraries open and to promote reading as well.

The Trouble with ISBNs

This is a post that I wrote for my work blog. ISBNs seemed like such a wonderful idea as a way to identify a unique work, but that was in the days of books being only in two formats, hardback and paperback. Now they could be anything, and the quantity of ISBNs are increasing rapidly. Perhaps it is time to have another think about them.

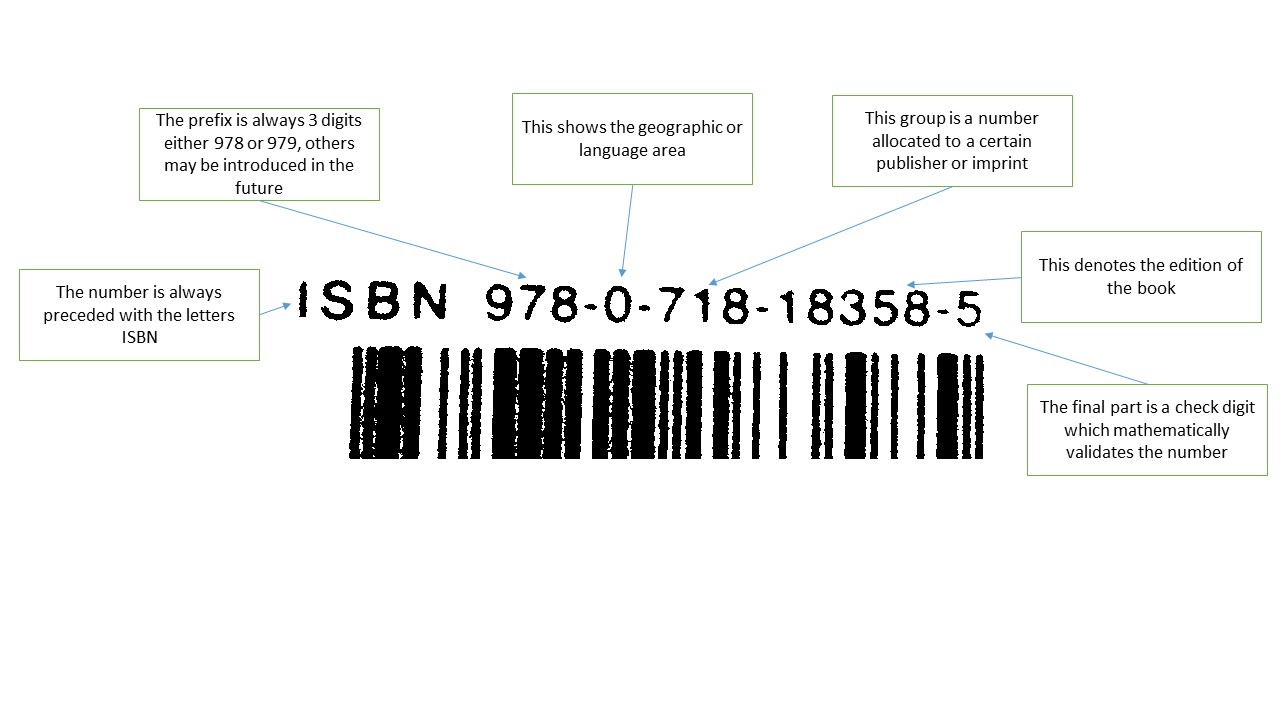

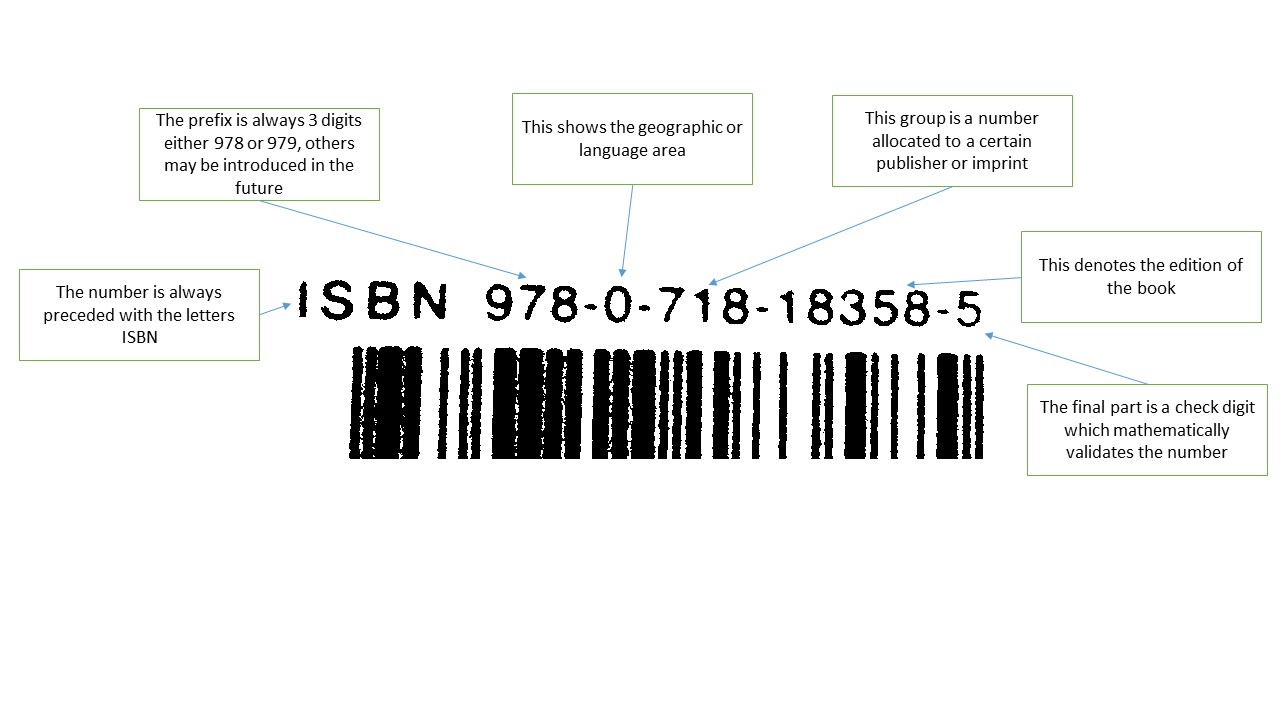

As a Librarian and shuffler around of books I have found International Standard Book Numbers (ISBN) to be really useful. Unlike what is portrayed in popular media the role of a librarian is not to stamp books and go "Shh" at people aggressively. It is our job to find things and to put things in the right order or place so that other people can find them too. I like to simplistically say that the purpose of a librarian is to sort things out into piles and that is a reasonable basic analogy of what we do. We take the things that hold knowledge, such as books, scrolls, documents, vinyl records, compact discs, digital texts, databases, e-books, anything and we make them "discoverable" by arranging them in ways that are easy to find. So books can be sorted out into the type of knowledge that they contain, such as History, Geography, Religion, Science and so on. There are many ways that things can be sorted, which is why there are many classification systems - Dewey Decimal, Library of Congress, for example. A book is assigned a particular classification number according to the knowledge that it holds, its content, so there can be many books attributed to the same number. Of course the titles and authors are different. So, what if you want to find a particular book? This is where ISBN numbers come in handy. The number is an official International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standard which was introduced by the book trade in 1970 to identify one publication or edition of a publication published by one specific publisher in one specific format. It was set up to allow automated machine reading of books, or "book like items", such as maps. The thirteen digit number is made up from smaller number groups that have been mathematically calculated to represent different elements. Let's take one of the numbers from the books in the photograph above.

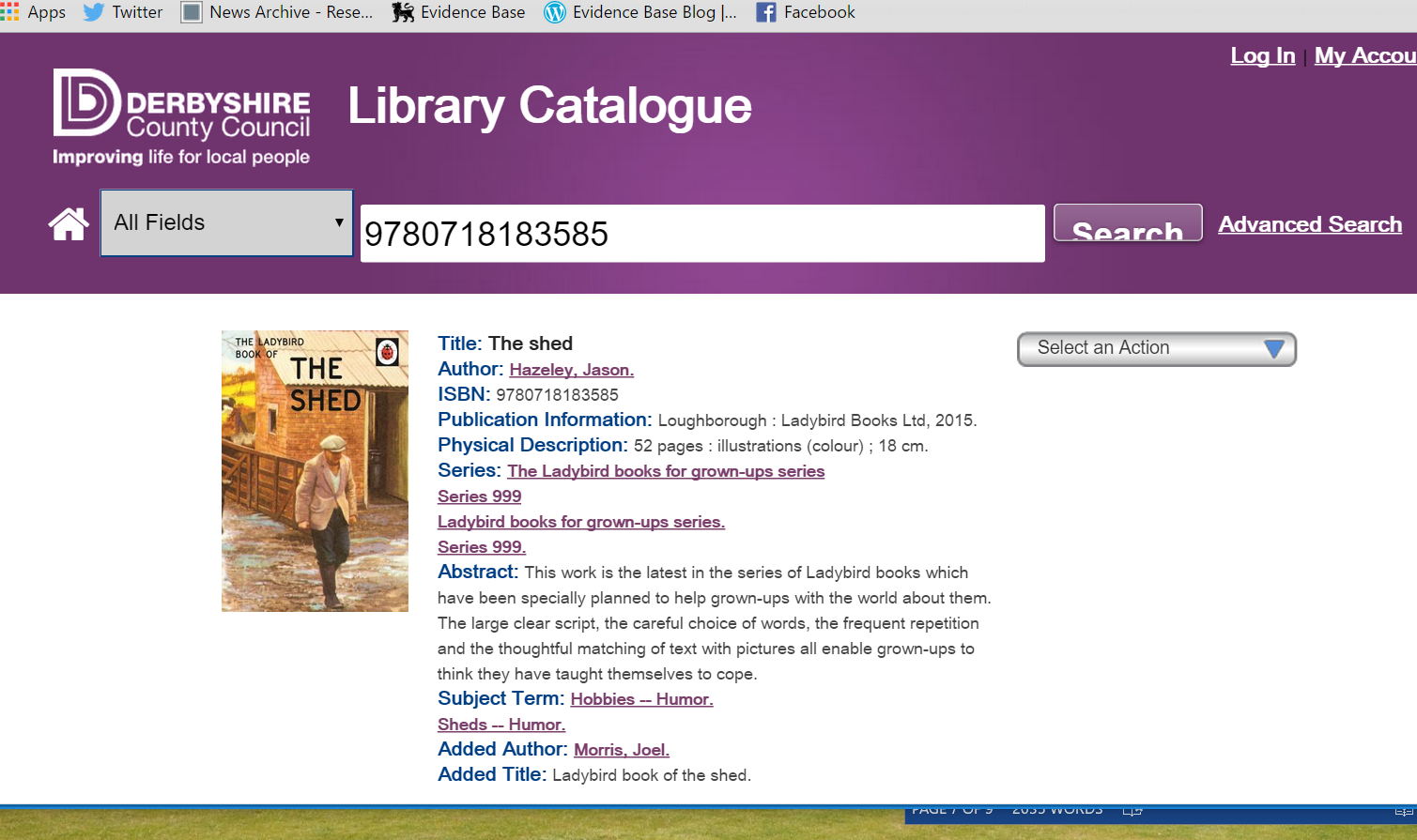

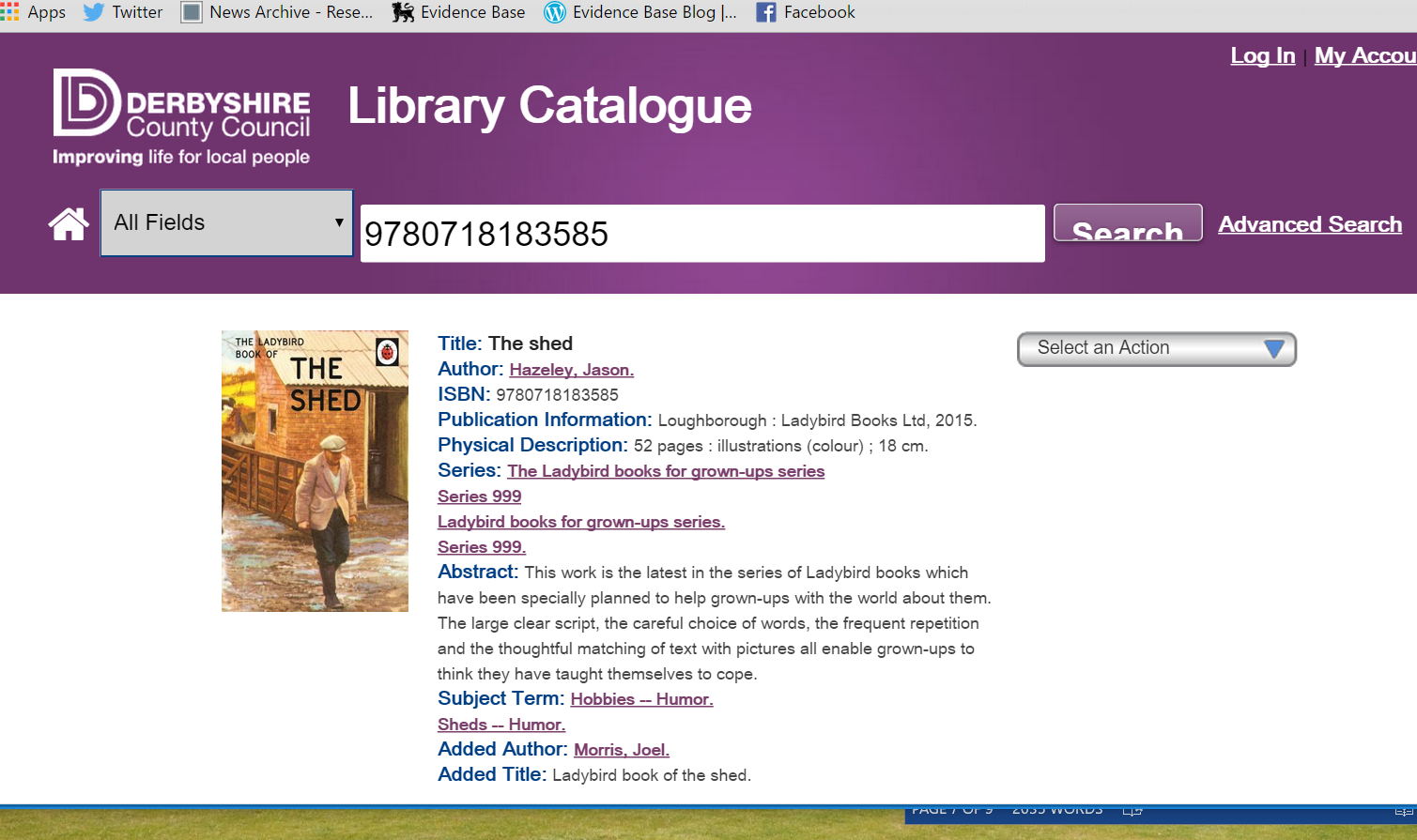

The number above shows that it is an ISBN (preface), it was published in the UK (geographic element), it was published by Ladybird Books (publisher or imprint) and it is this particular book (edition). In fact it is a hardback book titled The Shed. The machine readable part of the ISBN is the bar code, which can be scanned by a supplier, bookshop staff or library staff to identify that particular publication. ISBNs are issued through national agencies and held on their databases. This means that if you know that you want to buy a copy of the Ladybird Book of the Shed and you have its ISBN number you can type that in to Amazon or a library catalogue you can find out where to buy or borrow it.

So each ISBN number is a way of identifying that a printed, hardback copy of the title "The Shed" written by J.A.Hazeley and J.P.Morris was published by Ladybird Books Ltd, Loughborough in 2015. If the publisher decides to sell a paperback or e-book version, or the author wants to update or correct the words or change the illustrations in a second edition, then each one would have a different number in that edition element. Great, perfect for identification - by a machine. Just imagine that you are a librarian you only want one copy of The Shed and you don't care whether it is hardback or paperback, or you are trying to make space on your selves and only want an e-book and all you have is a long list of numbers and you can't work out which is the e-version, which the paperback and which is the one with different pictures. You see, the "edition " part of the numbers is a unique grouping just for that instance of publication. It is not a code that means e-book, or hardback, or third edition. This is the problem with ISBN, they are just too unique sometimes.

What is needed is an identifier for the intellectual output of that book, whatever the format. Now, I am not very well acquainted with these, but in searching for information for this blog post I have come across International Standard Text Code (ISTC) identifiers. This appears to be a number allocated to the textural content of something, no matter what is wrapped around the outside, metaphorically. So, perhaps these are the numbers to use at a time when any piece of text could available anywhere in any format and the variety of format choice just keeps growing.

This blog was first published on 24th March 2017 in Evidence Base Blog https://ebasebcu.wordpress.com/2017/03/24/the-trouble-with-isbns/

As a Librarian and shuffler around of books I have found International Standard Book Numbers (ISBN) to be really useful. Unlike what is portrayed in popular media the role of a librarian is not to stamp books and go "Shh" at people aggressively. It is our job to find things and to put things in the right order or place so that other people can find them too. I like to simplistically say that the purpose of a librarian is to sort things out into piles and that is a reasonable basic analogy of what we do. We take the things that hold knowledge, such as books, scrolls, documents, vinyl records, compact discs, digital texts, databases, e-books, anything and we make them "discoverable" by arranging them in ways that are easy to find. So books can be sorted out into the type of knowledge that they contain, such as History, Geography, Religion, Science and so on. There are many ways that things can be sorted, which is why there are many classification systems - Dewey Decimal, Library of Congress, for example. A book is assigned a particular classification number according to the knowledge that it holds, its content, so there can be many books attributed to the same number. Of course the titles and authors are different. So, what if you want to find a particular book? This is where ISBN numbers come in handy. The number is an official International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standard which was introduced by the book trade in 1970 to identify one publication or edition of a publication published by one specific publisher in one specific format. It was set up to allow automated machine reading of books, or "book like items", such as maps. The thirteen digit number is made up from smaller number groups that have been mathematically calculated to represent different elements. Let's take one of the numbers from the books in the photograph above.

The number above shows that it is an ISBN (preface), it was published in the UK (geographic element), it was published by Ladybird Books (publisher or imprint) and it is this particular book (edition). In fact it is a hardback book titled The Shed. The machine readable part of the ISBN is the bar code, which can be scanned by a supplier, bookshop staff or library staff to identify that particular publication. ISBNs are issued through national agencies and held on their databases. This means that if you know that you want to buy a copy of the Ladybird Book of the Shed and you have its ISBN number you can type that in to Amazon or a library catalogue you can find out where to buy or borrow it.

So each ISBN number is a way of identifying that a printed, hardback copy of the title "The Shed" written by J.A.Hazeley and J.P.Morris was published by Ladybird Books Ltd, Loughborough in 2015. If the publisher decides to sell a paperback or e-book version, or the author wants to update or correct the words or change the illustrations in a second edition, then each one would have a different number in that edition element. Great, perfect for identification - by a machine. Just imagine that you are a librarian you only want one copy of The Shed and you don't care whether it is hardback or paperback, or you are trying to make space on your selves and only want an e-book and all you have is a long list of numbers and you can't work out which is the e-version, which the paperback and which is the one with different pictures. You see, the "edition " part of the numbers is a unique grouping just for that instance of publication. It is not a code that means e-book, or hardback, or third edition. This is the problem with ISBN, they are just too unique sometimes.

What is needed is an identifier for the intellectual output of that book, whatever the format. Now, I am not very well acquainted with these, but in searching for information for this blog post I have come across International Standard Text Code (ISTC) identifiers. This appears to be a number allocated to the textural content of something, no matter what is wrapped around the outside, metaphorically. So, perhaps these are the numbers to use at a time when any piece of text could available anywhere in any format and the variety of format choice just keeps growing.

This blog was first published on 24th March 2017 in Evidence Base Blog https://ebasebcu.wordpress.com/2017/03/24/the-trouble-with-isbns/

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)